I have identified the so-called “foundation structure” of the Newport Grant House as a lime kiln on the basis of two vents in the north and south sections that nobody else has seemed to notice. It was the opinion of historian James Isham (1895) that the Old Stone Tower had to be a Colonial windmill on the basis of his belief that the foundation of the Grant House had mortar and arches with triangular keystones — just like the Newport Tower; and the Colonial Grant House was built circa 1670. Therefore, the Old Stone Tower had to have been built at the same time. My investigation of the photographic archive clearly indicates that there were three sections of an ancient lime kiln; and these are out of alignment with the later Colonial House. Also, Isham noted that Colonial builders often reused abandoned foundations from earlier structures. Prior to my research, nobody has found the industrial-grade lime kiln that was needed to produce lime mortar from oyster shells in sufficient amounts to provide the five tons of lime mortar that was needed to erect the forty-ton Stone Tower. This kiln would appear to be the missing kiln. Anyway, news of this development might provoke a renewed look at the evidence.

Gunnar. Thompson, Ph.D., Chief Archaeologist discovergunnar@hotmail.com

New World Discovery Inst. www.marcopoloinseattle.com

7516 36th Ave. NE Seattle, WA 98115-4821 USA mobile 360-643-1709

January 25, 2015

To: Editors, Curators, Historians, & Folks who are just plain curious

Research Update Bulletin

Ancient Medieval Lime Kiln at Newport, Rhode Island

Examination of Sueton Grant House demolition photographs in 1898 has revealed the presence of a 14th century Norman-Scottish lime kiln. It was incorporated into a Colonial Mansion built by Jeremy Clarke in about 1670. Historian Norman Isham noted in 1895 that the masonry of the foundation archway was identical in style and composition to the masonry used in building “the Old Stone Tower” – still standing in Touro Park.

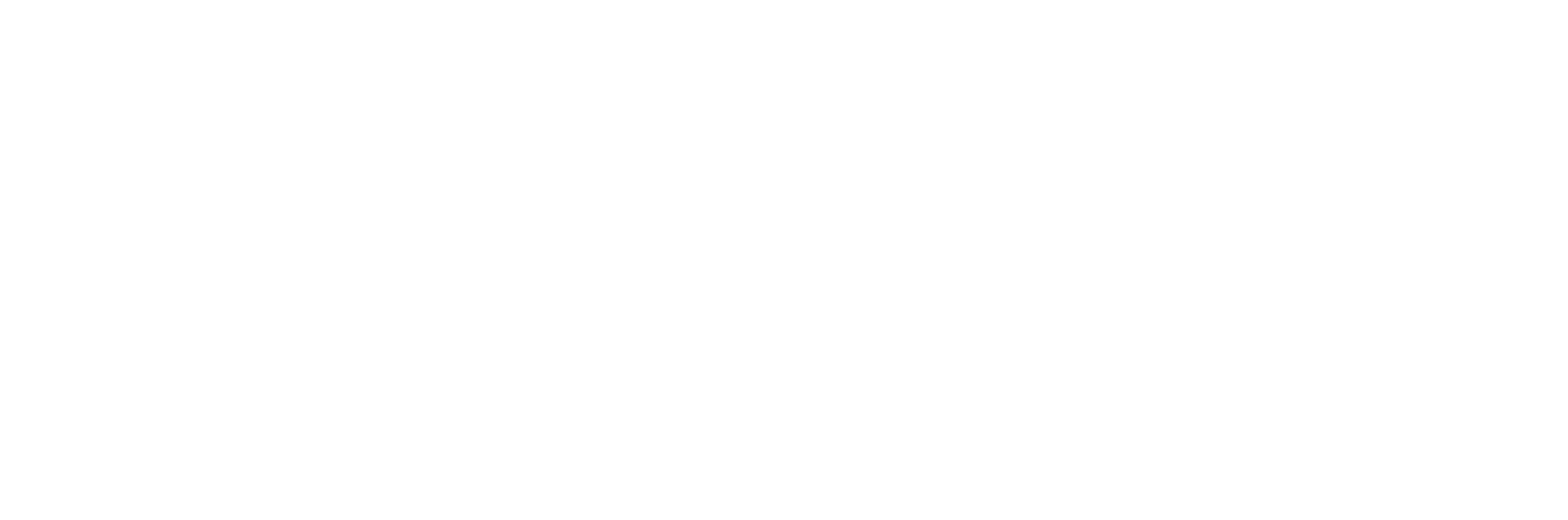

Photographs provided by the N.H.S. Archivist, Jennifer Robinson, reveal that the foundation structure is composed of three separate units – each having a distinctive eclectic, accordion-shaped arch with a triangular keystone. The foundation structure was originally used as an industrial-grade lime kiln. It was evidently constructed to make oyster-shell lime mortar when the Old Stone Tower was erected between 1370 and 1400. An artist’s reconstruction of the kiln is shown below in Figure 1.

The Colonial builder used the preexisting medieval lime kiln sections as a convenient foundation for three chimneys that were built above the ground floor. Photos show that the chimney superstructure is out-of-alignment by a meter on the east side; and this indicates that the foundation units of the kiln were not originally planned as part of a house foundation. Use of the structure as a kiln was determined by photos that revealed the presence of distinctive lime-kiln “vents.” These are situated above the north and south archways. These vents are common in medieval kilns that were built in the British Isles. Foundation vents of this type are otherwise totally unknown in Colonial New England.

Figure 1. Medieval Lime Kiln at Newport, Rhode Island c.1370.

Bulletin may be copied and distributed freely. Contact author for more information.

Mystery Solved! The “Lime Mill” that Built the Tower

Discovery of Newport’s Missing Industrial Lime Kiln

Gunnar Thompson, Ph.D.

New World Discovery Institute

January 22, 2015

Introduction

At some distant and controversial point in Newport’s Past, a team of experienced stone builders from the British Isles constructed a round tower in the scenic preserve that is known today as Touro Park. Were these renegade artisans the same bunch of Colonial philosophers who bequeathed to Rhode Island a passion for freedom of religion and justice? Were they a band of marooned Templar Masons from 14th century Scotland? Or were they just a random gang of professional handymen that Governor Benedict Arnold selected to build a more-durable stone mill to replace a wooden windmill that blew down in the furious Windstorm of 1673?

Until now, most historians have favored the “Windmill Theory;” but that enduring explanation is about to be replaced by one that is better-suited to the facts.

In April of 2014, an anonymous Patron of the Arts commissioned archaeologists and historians at the New World Discovery Institute to take a fresh look at the evidence. We were asked to determine if it was possible to reconstruct a new scenario of what really happened during those murky eons long ago when the City of Newport began to rise up from the marshes along Narragansett Bay. We are pleased to announce that we have found evidence of a previously unrecognized stone structure that was hidden away for many centuries beneath the skirts and girdle of an old Colonial mansion.

This investigation has been undertaken with the invaluable assistance of Jennifer Robinson at the Newport Historical Society and Museum. The Museum is located on Touro Street – not far from the spectacular and mysterious Old Stone Tower, or as some say: “the Old Stone Mill.” Ms. Robinson’s familiarity with the Photographic Archive enabled her to pinpoint key evidence from a collection of thousands of items. She identified for our research a series of snapshots that have been dated to 1898. They were taken by a professional photographer who was intrigued by the unusually grandiose stone and brick “chimney structure” that emerged from behind a cloak of plaster and lath that was removed when the dilapidated Sueton Grant House was demolished and hauled away to the City Dump. This incidental and fortuitous photo-shoot – more than a century ago – was pivotal to our investigation. It was already determined by Norman Isham’s research in 1895 that the same masons who built the Old Stone Tower also built the chimney foundation in the Grant House. If we could identify new clues from these old photographs, then there was a chance we could unlock the secrets to a mystery that has endured for several hundred years: “Who built the Tower?”

New Clues in the N.H.S. Photographic Archive

The Old Stone Tower is America’s Oldest Monumental Building erected by European masons. Whether it was built before, or after, the Columbus Voyage of 1492 is of pivotal importance to our understanding of American History. Hence, the origin of the Newport Tower has been an enduring dilemma for historians.

The Tower is a circular structure of stone masonry that was erected above an arcade level consisting of eight stone pillars. The approximate height is 28-feet (about 8.5m); the outside diameter varies from about 24 to 25-feet (7.3m); and the wall thickness is about 3-feet thick (or .91m). The walls are unusually wide for Colonial structures; and they constitute an enormous amount of weight that is carried by the eight pillars.

Part of the structure includes buried foundation stones that lie beneath each of the eight pillars. The approximate weight includes about 40 tons of stones. There is an additional weight of about 5 to 8 tons of cement. Chemical testing and magnification of surface material indicates that the lime used in making the mortar was obtained from “burned” or roasted oyster shells. This was a common source for mortar in most Colonial buildings during the early 17th century – as the shells were readily available in waste dumps at nearby Native villages. Remains of a small, six-foot diameter lime kiln have been excavated at the James Town archaeological site in Virginia dating to the early 1600s. A kiln of this size was sufficient for producing about four sixty-pound bags of lime; and this would supply enough mortar (mixed with sand) to build several small ovens or a basic house chimney. However, the typical kilns used by early European settlers in the 17th century were entirely inadequate for the demands of a structure like the Old Stone Tower at Newport. Erecting a forty-ton stone tower would have required the operation of an “industrial-grade” lime kiln.

One of the glaring problems with the early history of Newport, Rhode Island, has always been the total absence of remains from a suitable lime kiln that was up to the task of providing lime mortar for building the Old Stone Tower when it was supposedly erected in 1673. By that point in time, most of the lime used in making mortar for chimney construction seems to have come from outside of the community – possibly from industrial kilns being operated at Providence or New Holland (later, New York City). Furthermore, the imported lime wasn’t made from oyster shells; it was made from roasting crushed limestone (which in modern times is the principle source of Portland cement). Small, oyster-shell kilns are difficult to find in the archaeological record, because most of the small stones were reused in chimneys. On the other hand, it is incredibly unlikely that residents of Newport during the mid-to-late 17th century would have even used oyster-shell lime mortar – when a supply of cheap limestone cement was readily available by ship from nearby sources.

A clue to this mystery was identified in one of the 1898 Sueton Grant House demolition photographs (P9745) from the N.H.S. Archive. The photo shows what appears to be a medieval-style foundation arch beneath the ground-floor Colonial fireplace and chimney. This incredible photo, showing a 14th century medieval arch beneath a Colonial fireplace (built in about 1650) was first published in a book by Antoinette Downing and Vincent Scully, The Architectural Heritage of Newport, Rhode Island 1640-1915 (1967, Plate 26). A drawing of this structure is presented with other illustrations at the end of this report. Two rectangular openings or “vents” are clearly visible right above the medieval arch. Vents of this type were common features of medieval lime kilns in the British Isles – although they were quite rare in Colonial and post-Colonial kilns of New England. The eclectic style of masonry in the foundation arch, featuring a triangular keystone in the center, was characteristic of Norman-Scottish and Irish construction in the British Isles during the 14th century. Use of oyster-shell lime cement was also common at the same time in Norman-Scottish construction.

As Norman Isham noted in 1895, the style of arches and composition of mortar used in the Grant House and the Old Stone Tower are identical. Thus, we are confident in concluding that the masons who built both structures were the same; and both were constructed at approximately the same point in time. The enduring notion among historians that the Old Stone Tower was built in 1673 – during the Colonial Era – has rested almost entirely upon a brief and casual mention in the Last Will of Benedict Arnold in 1675 that he owned the “stone-built wind milne.” He certainly owned the structure – as it was situated on his property; and he certainly regarded the Tower as being a “windmill.” Indeed, the building was similar in size and shape to common, stone-built windmills in England and Holland. These mills generally used a rotating turret top that housed the wind sails (or propeller) that operated the gearbox and grindstone. However, rotating tops required special tracks and gears that were not available in New England until the beginning of the 18th century.

Almost identical masonry to that used in building the Old Stone Tower can be seen in 14th century Norman-Scottish ruins in the Orkney Islands and at the Scottish-built Hvalsey Church in Greenland. However, aside from the two contemporaneous buildings at Newport – using eclectic masonry with triangular keystones – the eclectic style with accordion-shaped arches and triangular keystones was entirely unknown in New England Colonial architecture. This is most-certainly an “intrusive” design feature in Newport architecture during the 17th century.

More surprises awaited us as we examined other photographs provided by the N.H.S. Archive Service. There were three similar arches in the foundation of the Sueton Grant House! Two of these had rectangular vents of the sort that were found in similar lime kilns in ruins dating to the medieval British Isles (11th to 14th centuries). Furthermore, the three “foundation arches” in the Grant House were built as separate structures – although they abutted against each other at the ends. This method of construction was not commonly encountered in the foundations that are designed for houses and chimneys. House foundations are typically interconnected along the entire perimeter of the superstructure that they are intended to support. However, separation of the three sections used for a kiln would not impair the function of burning or cooking oyster shells; and the presence of cracks between the three units could be explained as providing expansion-and-contraction joints in a structure that had to allow for frequent and considerable heat and cooling. An industrial kiln of this sort functioned a lot like a blast-furnace: the oyster shells were baked by a continuous blast of hot air and flames over a period of three consecutive days. The Newport lime kiln was probably fired by coal (obtained either locally or imported from Fife or Baffin Island). A single firing of oyster shells would produce several thousand pounds of lime. Thus, we have identified evidence of a structure at Newport that was suitable for “milling” adequate amounts of lime that were needed to build the Old Stone Tower.

Conclusions

Extensive Internet research regarding lime kilns, masonry styles, and arches in Colonial America and Medieval Europe confirms the probable time of construction for the Old Stone Tower as being the late 14th century. The masons were most-likely Norman-Scottish – that is, they were trained in masonry traditions of Northern Scotland (which at the time was still regarded as a Nordic Province). Between 1365 and 1410, agents of Denmark and the Kalmar Union were involved in the resettlement of refugees from the Eastern Settlement of Greenland. The Settlement was a Western Province of Norway (and hence also of the Kalmar Union that consisted of Denmark, Sweden, Norway, and the Western Province of Landanu – that is, the “New Land”).

Naturally, Queen-Regent Margaret Atterdag and her successor, Erik of Pomerania, were deeply concerned about the welfare of their distant Christian subjects; and their care and protection were under the direct responsibility of the current Earl of the Orkney Islands – Prince Henry Sinclair. About 4,000 farmers were desperate to escape from the Arctic onslaught of the Little Ice Age. As they had no suitable oceangoing vessels to carry their belongings to new homes in the southern territories along the Eastern Seaboard, they were entirely dependent upon Norman-Scottish merchants, or perhaps Hanseatic sea captains, for ferry service. As the owner of a merchant shipping company, Sinclair was in a position to provide ferry service – which was probably done with the condition that farmers pay for their transport by turning over a portion of future earnings from goods – such as stockfish and turkey corn – that were produced for transport to the markets of North European ports.

Giovanni Verrazano’s Report in 1524, which mentions “a white Native Tribe” and residents of Narragansett Bay who were “inclined to whiteness” suggests that one of the destinations of refugee farmers included the shores of Narragansett Bay. Doubtless, Nordic refugees who were transplanted to this region soon lost their ethnic and racial distinctions by merging with the local Narragansett and Wampanoag People. Legends or reports concerning the presence of a hybrid Native-European Colony in this region were probably a factor in the decision by Gerhard Mercator to identify “Norombega City” as the Capital of a European Colony alongside the shores of Narragansett Bay on his World Map of 1569. Other new settlements included Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, New York, and the Carolinas. Thus, Colonial settlers reported numerous contacts with “White Indians,” Welsh, Irish, and Nordic residents who were eager to trade furs and fish for coveted iron tools and fabrics from Europe. These early European settlers in the New World provided a “cultural bridgehead” that facilitated the survival of new immigrants from the Old World.

———————————————-

References:

Downing, Antoinette F., & Vincent J. Scully. The Architectural Heritage of Newport, Rhode Island 1640-1915. New York: American Legacy Press, 1967 (Plate 26).

Isham, Norman. Early Rhode Island Houses. Providence: 1895.

Morrison, Hugh. Early American Architecture. New York: Oxford U. Press, 1952, 95.

For further information, visit: http://www.marcopoloinseattle.com

NHS photographs available from JRobinson@newporthistorical.org (401) 846-0813

Illustrations

Figure 1. A medieval coal-fired lime kiln was constructed between 1370 and 1400 at Newport, Rhode Island. This kiln was used initially by Norman-Scottish masons to produce lime that was needed for mortar used in building the Old Stone Tower and perhaps a house for the Greenland Bishop that was located on the waterfront street (later, Thames Street). This reconstruction is based on NHS photographs taken during the 1898 demolition of the Sueton Grant House that was built by Jeremy Clarke circa 1670. Note presence of three separate sections and vents for a lime kiln located above the arch. These three sectional structures were not identified in a “floor plan” by Bergner (in Downing & Scully, 1967, Plate 26). Thus, they were effectively concealed from subsequent scholars. This mistake has introduced a fatal flaw in the study of evidence by most historians who simply assumed there was a direct correspondence between the three foundation arches and the three Colonial fireplaces built above them. The third fireplace was not part of the original structure; it was added later as an addition. This addition caused is out of alignment with the foundation.

Photographs indicate that vents were present in both the north and south sections of the foundation-level kiln. The roadway leading to the open western side was used for inserting coal or wood and subsequently removing the burned oyster-shells after the burn. The eastern archway was used to stoke the fire with coal or wood during the burn.

Figure 2. Small, “backyard” versions of lime kilns were used to fire sufficient oyster shells to make the equivalent of four sixty-pound bags of modern cement. This would be about what was needed to construct the standard bread oven or a small fireplace in a single-room log cabin. Archaeologists working for the NPS uncovered such a structure at the Jamestown Settlement Site in Virginia dating to c.1650.

(National Park Service reconstruction, Jamestown Kiln, after Project Gutenberg; http://media. finddictionary.com/pictures/151/17/4503.jpg – accessed December 2014)

Figure 3. Colonial, top-loading Industrial-Grade Lime Kiln

Major stone-building projects, such as the Old Stone Tower in Newport, were impossible without the production capacity of an industrial mill. Layers of crushed limestone interspersed with coal, charcoal, or wood, were loaded from the top. After the burn, the converted lime material was removed by shovel, bucket, and barrel. Stones around the upper part of the kiln were never cemented – making removal easier.

Figure 4. Demolition Photo (1898) of the Sueton Grant House in Newport, Rhode Island, shows Colonial fireplace erected above a prior, medieval lime kiln at the foundation level. Lower archway is made in the Norman-Scottish tradition using an eclectic, accordion-shaped arch with distinctive triangular keystone. This style of arch was otherwise unknown in Colonial architecture. Dark rectangles above arch are lime-kiln vents.

(After photo from Newport Historical Society Archive, P9745; Downing & Scully, 1967, Pl.26)

Figure 5. Industrial Lime Kiln at Murlouch Bay, Ireland was built into a hillside. The backside of this kiln provided a route of access for inserting crushed limestone and the fire charge of coal or wood. Note positions of vents above the arches. This was a common style of kiln in medieval Ireland and Scotland.

(After a photo from http://lowtechmagazine. com/2013/09/ lime-kilns.htm)

Figure 6. Medium sized Scottish lime kiln has vent above front access doorway. Most lime kilns used semicircular, Romanesque archways for access. In this case, a stone lintel spans the front opening. This example is located at Badenyon in Aberdeenshire, Scotland.

(http://www.wikipedia/wiki/Aberdeenshire)

Figure 7. The Old Stone Tower at Newport (left) is a circular stone structure that rests upon eight round pillars. Hugh Morrison (1952, 95) noted that: “The Newport Tower has little significance in the history of Colonial architecture. Nothing quite like it had been built before, or was ever built afterward. … Colonial architecture was entirely traditional and almost entirely unprogressive.” In other words, the structure is entirely intrusive in its design. By the 17th century, Europeans living in the post-Renaissance typically built with precisely cut stones or ceramic bricks. The eclectic, “make-do” style building walls and chimneys with materials at hand was quickly abandoned in Colonial structures. Arches of the Newport Tower (center) are eclectic and medieval Norman-Scottish in design. NHS photographs confirm that all known Colonial arches and load-bearing spans at Newport used uniformly-cut stones, standardized ceramic bricks, or oak beams (right).

Figure 8. “Jerome’s Arch,” a distinctive Norman-Scottish design comprising eclectic, accordion-shaped arches with triangular keystones, was built by Scottish masons at Eynhallow Church, Orkney Isles, and at Hvalsey, Greenland (top row). Similar medieval arches are seen at Newport’s Grant House lime kiln and Old Stone Tower (bottom).

Please visit Mr. Thompson’s incredible article on Early New World Maps here

As well as his website www.marcopoloinseattle.com

Books by Gunnar Thompson:

American Discovery is the best introduction to ancient New World voyages you can find on the planet. This elegant tour-de-force includes chapters on early voyagers from Indo-Sumeria, Japan, Minoan Crete, Phoenicia, Egypt, Nubia and West Africa, China, Greece & Rome, Ireland & Wales, Polynesia, Arabia, Scandinavia & Germany, and Renaissance Europe. Fully illustrated with maps, artifacts, ships, plant diffusion, legends, and maritime adventures. Suitable for young adults or general adult readers. 327 pages. Please purchase here or at lulu.com.

American Discovery is the best introduction to ancient New World voyages you can find on the planet. This elegant tour-de-force includes chapters on early voyagers from Indo-Sumeria, Japan, Minoan Crete, Phoenicia, Egypt, Nubia and West Africa, China, Greece & Rome, Ireland & Wales, Polynesia, Arabia, Scandinavia & Germany, and Renaissance Europe. Fully illustrated with maps, artifacts, ships, plant diffusion, legends, and maritime adventures. Suitable for young adults or general adult readers. 327 pages. Please purchase here or at lulu.com.

Viking America tells the story of Roman trade with ancient America, King Arthur’s Colony of New Albion, Welsh immigration in the 6th century and expansion into the Ohio Valley. King Haakon IV established a transatlantic trading alliance in 1264. During the Medieval Warm Period, transatlantic trade was controlled by the Hanseatic League. In the 13th century, Queen Margaret of the Kalmar Union led an effort to restore Nordic trade with the Western Provinces. Prince Henry Sinclair and Templar Knights overcame pirates in Vinland; and they established a lasting Colony of Norumbega. Fully illustrated with maps, artifacts, ships, plant diffusion, legends, and maritime adventures. Suitable for young adults or general adult readers. 325 pages. Please purchase here or at lulu.com.

Marco Polo in Seattle tells the story of the Polo Brothers Spy team. Nicolo, Maffeo, and Marco were sent by Pope Innocent IV to China in order to learn the secrets of the Mongolian Emperor Kublai Khan. Marco was assigned the job of accompanying mapping expeditions to the American West Coast between 1280 and 1292. The Polos brought back to Venice maps of Alaska, California, and Peru – as well as plans for making the first muskets in Europe. Fully illustrated with maps, artifacts, ships, plant diffusion, legends, and maritime adventures. Suitable for young adults or general adult readers. 305 pages. Please purchase here or at lulu.com.

Marco Polo’s Daughters tells how Fantina, Bellela, and Moretta helped make their father’s book about the Orient a bestseller in Europe. Includes maps and letters about Marco Polo’s secret voyages to the New World. Marco’s secret voyages extended from Alaska and the Northwest Passage to the West Coast of Washington, Oregon, California, Mexico and Peru. Fully illustrated with maps, artifacts, ships, plant diffusion, legends, and maritime adventures. Suitable for young adults or general adult readers. 395 pages. Please purchase here or at lulu.com.

Marco Polo’s Daughters tells how Fantina, Bellela, and Moretta helped make their father’s book about the Orient a bestseller in Europe. Includes maps and letters about Marco Polo’s secret voyages to the New World. Marco’s secret voyages extended from Alaska and the Northwest Passage to the West Coast of Washington, Oregon, California, Mexico and Peru. Fully illustrated with maps, artifacts, ships, plant diffusion, legends, and maritime adventures. Suitable for young adults or general adult readers. 395 pages. Please purchase here or at lulu.com.

Francis Drake & the Port Townsend Mystery tells how the English privateer explorer sailed along the West Coast of America using a clock to prepare a navigational chart. This map is the earliest scientific map of the West Coast. Drake explored the Salish Sea (or Strait of Juan de Fuca) as a possible site for a new colony. Then he sailed on to San Francisco Bay where he left behind a third of his crew. Fully illustrated with maps, artifacts, ships, plant diffusion, legends, and maritime adventures. Suitable for young adults & general adult readers. 227 pages. Please purchase here or at lulu.com.

Secret Voyages has chapters on the female pharaoh, Hatshepsut, King Solomon, Marco Polo, the Franciscan Friar Nicholas of Lynn, Chinese Admiral Zheng He, the Portuguese Spy – Martin Behaim, and the Nordic adventurer Roald Amundsen. These vignettes reveal that maps, artifacts, and other clues can enable us to reconstruct ancient voyages that were kept secret due to the importance of geographical information to medieval societies. Fully illustrated with maps, artifacts, ships, plant diffusion, legends, and maritime adventures. Suitable for young adults or general adult readers. 305 pages. Please purchase here or at lulu.com.

Ancient Egyptian Maize tells the story of how the New World crop spread all over the planet prior to the voyages by Columbus and other Renaissance Europeans. Several chapters highlight voyages by Egyptian traders to the mysterious Land of Punt. The principal sponsor of these expeditions was the female Pharaoh, Hatshepsut. Fully illustrated with maps, artifacts, ships, plant diffusion, legends, and maritime adventures. Suitable for young adults or general adult readers. 205 pages. Please purchase here or at lulu.com.

The Friar’s Map of North America 1360 AD

Did Monks come to America before Columbus? Like New condition published in 1996.

Very Good++ condition published in 1998 and signed by the author. Also available a Like New condition copy.

Good+ condition hardcover and dustjacket published in 1989. Also availble is a Very Good condition copy with a Good+ dustjacket.

The Diffusion Issue

George F. Carter, Stephen C. Jett, Gunnar Thompson, James Brett, Donald L. Cyr

Very Good+ condition published in 1991, written by incredible men.